Learning and Decision Making

I recently watched a podcast featuring Richard Sutton, widely regarded as the father of reinforcement learning, who criticized the current architecture of large language models (LLMs) as a dead end, an approach he believes cannot lead us to true artificial general intelligence (AGI). Richard argued that this paradigm has reached its limits, as these models merely learn to predict the next token or word from vast amounts of human generated text. In essence, LLMs imitate the appearance of intelligence and mimicking human-like responses rather than developing genuine understanding. Their design, he suggested, stands in stark contrast to how intelligence emerges in nature.

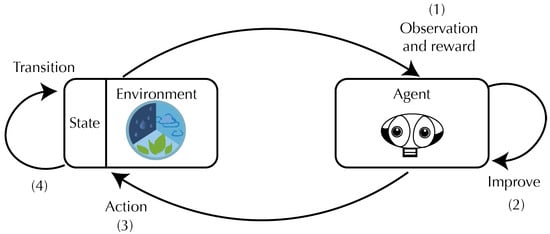

In the natural world, learning is grounded in trials and errors, a continuous feedback loop of action, consequence, and adaptation. Animals learn not through imitation, but by interacting with their environment and adjusting their behavior based on the outcomes of their actions. The process of exploration and feedback forms the foundation of true intelligence. In contrast, current LLMs are trapped in a world of static data, mimicking patterns in human language without engaging with the physical realities those words describe.

Human intelligence represents a hybrid of both imitation and feedback. Early learning relies heavily on imitation, for instance children copy speech, gestures, and social behaviors. But as they grow, they refine this knowledge through experience and feedback from the environment. The fusion of imitation and feedback creates a more dynamic form of intelligence, capable of creativity, abstraction, and reasoning.

At present, our understanding of superintelligence is still narrow. Systems like AlphaGo and advanced chess engines have demonstrated extraordinary capabilities, yet they exist only within closed environments defined by clear objectives and measurable outcomes. They surpass human intelligence because their feedback loops with millions of simulated games or moves which are accelerated far beyond human capacity. However, this kind of intelligence does not generalize beyond its domain. Real-world human problems are not games as they lack clear goals and well-defined success conditions.

This ambiguity is the key barrier to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) as human tasks are often subjective, context-dependent, and open-ended. The assumption that there is always an “optimal decision” is an illusion. Decision-making in life is not about selecting a perfect choice from a set of options, it is about navigating uncertainty, adapting as outcomes unfold, and learning from imperfect experiences. The success of a decision depends less on the choice itself and more on the execution and adaptation that follow. This makes it impossible to determine optimality in advance.

AI, therefore, can only serve as an assistant. It can analyze scenarios, propose possible actions, and simulate outcomes, but it cannot identify the singular “right” solution. Humans are, in effect, outsourcing the thinking process to AI and using it as a tool for reasoning under uncertainty. This growing blind faith in LLMs is a genuine concern, as illustrated by the recent appointment of an AI “minister” in the Albanian government. Such heavy reliance risks undermining human creativity and critical thinking. Just like the TikTok algorithm, LLMs inherently generate standardized and homogenized responses. Over time, this algorithmic reasoning could narrow intellectual diversity, trapping society in a cycle of uniform and predictable thought.

This raises deeper questions: can LLMs ever develop genuine intelligence and understanding grounded in physical reality? And how should humanity establish principles that ensure AI is used for greater good? I have some speculations and will explore these ideas further in my next post.